Cross-build injection attacks: how safe is your build?

Imagine a world in which people blindly trust binaries uploaded to the internet by random strangers. Certainly not a world in which we as software engineers want to live. Except that many of us, including myself, do exactly that. On a regular basis. In our most precious environment: the software build process.

Update 2012-08-22: I've posted a follow-up on how to verify dependencies using PGP.

What follows is a tale of trust and naiveté, leading to vulnerabilities that we rarely talk about: the injection of malicious code into our own applications. Enter the wonderful world of 'Cross-build injection attacks' (XBI). Aptly named by Fortify (pdf) after website attacks such Cross-site Scripting and Cross-site Request Forgery, but without even nearly as much mindshare among developers.

Typical builds

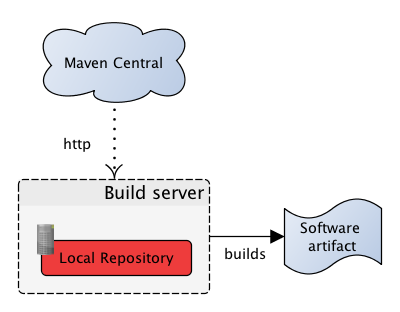

Most software uses other software: libraries and frameworks enable us to quickly write the good stuff rather than the tedious and boring stuff. This implicitly means we trust the code inside these libraries, based on for example the credentials of the library authors or because we've used it before (or dare I say, because we've verified the sourcecode of said library...) But how do these libraries physically end up in our own software? Let's look at the typical setup of a Java project (the remainder of this post discusses XBI on the Java platform, but towards the end we'll see that other platforms have similar issues). Most projects use Maven as their build system, or one of the fancier new build tools like SBT or Gradle which rely on the same Maven repository infrastructure. This results in the following situation:

Maven has, for all its warts, provided us with a centralized canonical repository called Maven Central that contains many popular Java libraries. That's a good thing. But how can we be sure that what Maven downloads into our local repository is actually what was put into Maven Central by the library authors? Or, put differently, how would an attacker exploit this system in order to inject malicious code into our builds?

Attacking a build

The first obvious XBI attack is to man-in-the-middle requests to Maven Central. Since Maven Central only allows http access (I guess https is cost-prohibitive CPU-wise when you are streaming binaries to the world for free), this is relatively easy. Maven does have a checksum facility, but an attacker can just man-in-the-middle the file containing the checksum as well, which is stored alongside the binary in Maven Central. In this sense, the checksums only help to detect transport problems and cannot be relied on to verify the authenticity of the binary.

Another, more involved XBI attack would be to 'poison' Maven Central by replacing binaries that are served. This only works when the security of the Maven Central servers is somehow compromised, which would be a big deal for everyone.

Cutting all ties

One obvious reaction to these threats is to not depend on Maven Central. Many companies I've worked with setup their own internal Maven repository, so the build server needn't be connected to the internet. Of course, the next question is: how do dependencies end up in this internal repository?

Indeed, by downloading them from Maven Central. The good thing is that you've decreased the attack surface since you only need to download once. But it's still not really satisfactory, since the attacks mentioned earlier still apply, albeit less so. Additional checks and measures before placing dependencies into the internal repository can help, but these are rarely in place. Looking at this survey only 50% of the companies have an open-source policy in place, and if there is one it is mainly concerned with legal aspects, not technical.

No, in practice, someone is tasked to mindlessly perform the download and shove it into the internal repository. At least now you have someone to scapegoat should it be malicious code, but really, this solves nothing. Also, this 'offline' workflow is sort of annoying during development, especially when you have manually chase transitive dependencies and do other things Maven would normally do automatically. But then again, security always has a cost.

Cryptography

Can we do better? Fortunately, yes. Starting three years ago, Maven Central requires PGP signing of uploaded artifacts. An .asc file containing the cryptographic signature is added alongside the binary. This means we can use the public key of the uploader to verify the signature derived from the binary with the author's private key. Of course, the public key should be obtained from a trusted source (such as MIT's public key server). Now we can be sure that we download the exact file that was uploaded by the library author. We're safe, even if the repository we download from has been compromised! Unless the artifact is older than three years, that is...

There's one downside: Maven does not check these PGP signatures automatically. A fully automated solution is offered by Sonatype with Nexus Professional, a commercial repository manager that can be installed inside a company. Didn't I just mention that security always has a cost?

Other platforms

I took the example of Maven and Maven Central because it's the eco-system I'm most familiar with. However, all platforms with automatic dependency management have to deal with this issue. Look, for example at this quote from the Ruby Gems manual:

1.3 Security Issues

Doesn’t this open a huge security hole? How can I trust the Gems

which are automatically downloaded from the net?

The same way you can trust all other code you install.

(I.e. ultimately, you can’t.)

Or take Perl's CPAN, which hosts Perl modules from just about anyone. Checksums are as good as it gets on CPAN. Many people even execute CPAN scripts as root for ease of use. Discussing this dire situation leads to nice quotes such as:

'Over the last 7 years, we haven't had any problems of this nature and hopefully it will remain that way ...'

or:

'How much can you trust code from CPAN? The bad news is that it is true that

there is little quality control on CPAN .. Technically, someone could place

malicious code on CPAN.'

In other words: don't sweat it, nobody would do such a thing, right?

Really?

I know, this whole post may sound far-fetched. But that doesn't make the threat less real. There are many high-profile software builds (think banks, government, law enforcement etc.) depending increasingly on open-source libraries distributed through the internet. In the end the only way to be really safe is to download the library sources, verify them by hand, build them from source and place them into your build. But then again, who has the resources to do that? I'm very curious if there have been actual XBI victims, either with Maven or similar build systems.