The Java Modularity Story

So you've got a growing Java application with a nice feature set. Unfortunately adding new features gets harder over time and things start breaking in unexpected places. Chances are that your applications is not as modular as it could be. Relax, it's not (just) your fault. Plain Java is notoriously lacking in the modularity department. But it doesn't have be this way.

Modularity leads to more maintainable, composable and extensible systems. When you have clearly demarcated module boundaries and explicit contracts between modules, life is good. Functionality can be tested in isolation, and divide-and-conquer can be applied at the code and team-level. This speeds up development, not just in the first year of the system, but throughout its whole lifecycle.

From architecture to software

So how do you get to that point? We'll get to a specific solution later, but first I want to take the time to define the problem clearly. Modularity plays a big role at many levels of abstractions. At the systems architecture level, we have Service Oriented Architecture. When done right, SOA means explicit and versioned public interfaces (mostly webservices) between loosely coupled subsystems that hide their internal details. These subsystems possibly even run on completely disparate technology stacks and are easily replaceable on an individual basis.

However, when building the individual services or subsystems in Java, a monolithic approach is often irresistible. Java's own runtime, rt.jar is unfortunately a prime example. Sure, you may partition your monolithic application into the three obligatory layers, but that's a far cry from true modularity. Just ask yourself what it would take to swap out the lowest layer of your application for a completely different implementation. Oftentimes, this would ripple through the whole application. Now, try thinking of how you would do this without disrupting the other parts of your application, when hot-swapping at run-time. Because why should this be possible in a SOA context, but not inside our applications?

True modularity

So what is this true modularity I alluded to in the preceding paragraph? Let me state some defining characteristics of a true module:

- a module is an independent unit of deployment (reusable in any context),

- it has a stable, reified identity (for example name and version),

- it states requirements (dependencies),

- it advertises capabilities for other modules to use while hiding implementation details.

Ideally, these modules live in a lightweight runtime environment that matches up the requirements and capabilities of modules for us according to our desired composition. In short, we want our application to use modules to get the good parts of a Service Oriented Architecture on a smaller scale. And not just on the whiteboard, but also while coding and running the application. We want our physical implementation to follow our logical design all the way through production. What's more, the composition of modules shouldn't be static: applications need to be resilient and extensible without downtime or full redeployment.

Objects: true modules?

What about the lowest layer of structural abstraction in Java: classes and objects. Doesn't OO provide identity, information hiding and loose coupling through interfaces in Java? Yes it does, to a degree. However, object identity is ephemeral and interfaces are unversioned. Classes are most certainly not an independent unit of deployment in Java. In practice, classes tend to get way too familiar with each other. Public means visible to literally every other class on the JVM's classpath. Which is probably not what you want for anything but truly public interfaces. To make matters worse, Java's visibility modifiers are weakly enforced (think reflection) at runtime.

Reuse of classes outside their original context is hard when nobody forces the cost of their implicit external dependencies on you. I can practically hear the words 'Dependency Injection' and 'Inversion of Control' racing through your mind now. Yes, these principles help to make dependencies of a class explicit. Unfortunately their archetypical implementations in Java still leave your application as a big ball of objects wired together statically at runtime by a big ball of configuration. I highly recommend reading 'Java Application Architecture: Modularity Patterns' if you wan to learn more about modular design patterns. But you'll also find that applying these patterns in Java without additional runtime enforcement of modularity is fighting an uphill battle.

Packages: true modules?

But then what is the unit of modularity in Java inbetween applications and objects? You could argue that packages must be it. The combination of package names, import statements and visibility modifiers (e.g. public/protected/private) gives the illusion that at least some of the characteristics of true modules are present. Unfortunately packages are purely a cosmetic construct, providing namespacing for classes. Even their apparent hierarchy is actually an illusion.

So yes, by all means use packages to structure your code base in logical chunks. Just don't count on packages to improve modularity beyond pretty names. To be fair, there are tools that can help with enforcing package dependencies through static verification at development time. But that's hardly a satisfying solution.

JAR files: true modules?

Surely the true unit of modularity for Java applications then must be JAR files (Jars). Well, yes and no. Yes, because Jars are the independent units of deployment for Java applications. No, because they fail on the three other characteristics. Jars have a filename, and sometimes a version in the MANIFEST.MF. Neither are part of the runtime model and hence do not form an explicit reified identity. Dependencies on other Jars can't be declared. You have to make sure any dependencies are on the classpath. Which, by the way, is just a flat collection of classes: gone is the link to the originating Jars. This also explains another big problem: any public class in a Jar is visible to the whole classpath. There is no 'jar-scope' modifier to hide implementation details inside a Jar.

All of the above means that Jars are a necessary, but not sufficient mechanism for modular applications. Many people are successfully building systems out of lots of Jars (by applying modular architecture patterns), managing the identities and dependencies with their favorite compile-time dependency management tool. Take for example the Netflix API, which is composed of 500 JARs. Unfortunately, your compile-time and run-time classpath will diverge in unforeseen ways, giving rise to the JAR-hell. Alas, we can do better than this.

OSGi bundles

Clearly, plain Java doesn't offer enough in terms of modularity. It's an acknowledged problem and with project Jigsaw there might be a native solution on the way. However, it has missed the Java 8 train (and Java 7 before that), so it will be quite some time before we can use it. If it ever arrives. Enter OSGi: a modular Java platform that's mature and battle-hardened. It is used by the likes of application servers and IDEs as the basis for their extensible architectures.

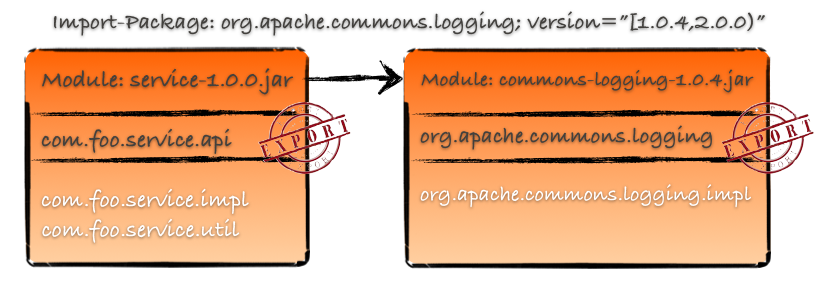

OSGi adds modularity as a first-class citizen to the JVM by amending Jars and packages with the necessary semantics to achieve all of our stated goals for true modularity. An OSGi bundle (module) is a Jar++. It defines additional fields inside a Jar's manifest for a (preferably semantic) version, bundle-name and which packages of the bundle should be exported. Exporting a package means you give the package a version, and all public classes of the package are visible to other bundles. All classes in non-exported packages are only visible inside the bundle. OSGi enforces this at runtime as well by having a separate classloader per bundle. A bundle can choose to import packages exported by another bundle, again by defining its imported dependencies in the Jar's manifest. Of course such an import must define a version (range) to get meaningful dependencies and guide the OSGi bundle resolving process. This way, you can even have multiple versions of package and its classes running simultaneously. A small example of a manifest with some OSGi parameters:

And the accompanying manifest for the service bundle:

Manifest-Version: 1.0

Bundle-ManifestVersion: 2

Bundle-Name: MyService bundle

Bundle-SymbolicName: com.foo.service

Bundle-Version: 1.0.0

Import-Package: org.apache.commons.logging;version="[1.0.4, 2.0.0)"

Export-Package: com.foo.service.api;version="1.0.0"

And there you have it: OSGi provides an independently deployable Jar with a stable identity, and the possibility to require or advertise dependencies (ie. versioned packages). Everything else is strictly contained inside bundles. The OSGi runtime takes care of all the gritty details to enforce this strict separation at runtime. It even allows bundles to be added, removed and hot-swapped at run-time!

OSGi services

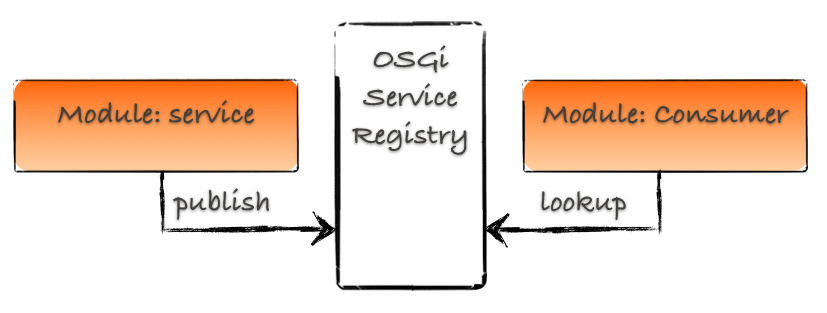

So, OSGi bundles take care of dependencies defined on the package level, and defines a dynamic lifecycle for bundles containing these packages. Is that all we need to create a SOA-like solution in the small? Almost. There is one more crucial concept before we can really have modular micro-services with OSGi bundles.

With OSGi bundles, you can program to an interface that is exported by a bundle. But, how do you obtain an implementation of this interface? It would be bad to export the implementing class, just so you can instantiate it in consuming bundles. You could use the factory pattern and export the factory as part of the API. But having to write a factory for every interface sounds… boiler-platey. Not good. Fortunately, there's a solution: OSGi services. OSGi provides a service-registry mechanism, where you can register your implementation under its interface in the service registry. Typically, you register your service when the bundle containing the implementation is started. Other bundles can request an implementation for a given public interface from the service-registry. They will get an implementation from the registry without ever needing to know the underlying implementation class in their code. Dependencies between service consumers and providers are automatically managed by OSGi in much the same way as the package-level dependencies are.

Sounds good, right? There's one slight bump in the road: using the low-level OSGi service API correctly is hard and verbose, since services can come and go at runtime. This is because bundles that expose services can be started and stopped at-will and even running bundles can decide to start and their services at any time. That's extremely powerful when you want to build resilient and long-lived applications, but as a developer you have to stand your ground. Lucky for us, many higher-level abstractions have been created to take care of this problem. So, when using OSGi services, use something like Declarative Services or Felix Dependency Manager (which is what we use in our projects) and create and consume micro-services with ease. You can thank me later.

Is it worth it?

I hope you agree with me that having a modular codebase is a worthy goal. And no, you don't need OSGi to modularize a codebase. Conversely, modular runtimes like OSGi can't rescue a non-modular codebase. In the end, modularity is an architectural principle that can be applied in almost any environment, given enough willpower. It takes additional effort to create a modular design. It's only natural to use runtime in which modules and their dependencies are first-class citizens from design-time through run-time to ease the burden.

Is it hard in practice? There definitely is a learning curve, but it's not as bad as some people make it out to be. Tooling for OSGi-based development has improved tremendously the past few years. Especially bnd and bndtools deserve a mention for this. If you'd like to get a feel for what it means to develop a modular Java application, watch this screencast from my co-worker Paul Bakker. He is also the co-author of an upcoming O'reilly book on this topic that you can preorder here.

Modular architectures and designs are increasingly getting attention. If you want to apply this now in your Java environment I encourage you to follow some of the links in this article and give OSGi a spin. Again, it won't come from for free. But remember: OSGi isn't hard, true modularity is.